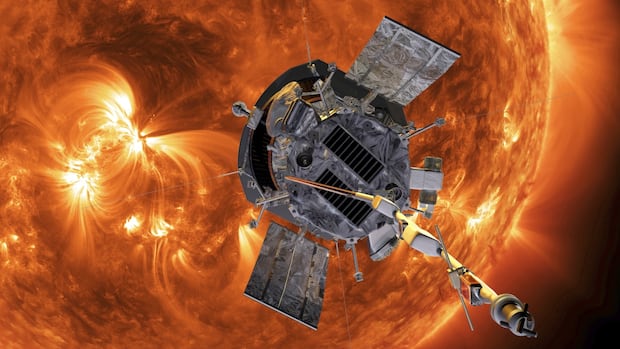

A NASA spacecraft may have made history, flying closer to the sun than any object sent before.

The Parker Solar Probe had been on course to fly around 6.1 million kilometres from the surface of the sun on Tuesday at 6:53 a.m. ET

But NASA will be out of contact with the probe for a few days, meaning it won’t know if it survived its pass by the sun until Dec. 27, when Parker is set to transfer another beacon tone to confirm its health, NASA said on its website.

“No human-made object has ever passed this close to a star, so Parker will truly be returning data from uncharted territory” Nick Pinkine, Parker Solar Probe mission operations manager at APL, said on the NASA website.

Quirks and Quarks7:37A NASA probe is going to touch the Sun for Christmas

“We’re excited to hear back from the spacecraft when it swings back around the sun.”

The Parker Solar Probe was launched in 2018 to get a close-up look at the sun. Since then, it has flown straight through the sun’s corona — the outer atmosphere visible during a total solar eclipse.

Its purpose is to trace the flow of energy, to study the heating of the solar corona and to explore what accelerates the solar wind.

Parker planned to get more than seven times closer to the sun than previous spacecraft, hitting speeds of 690,000 km/h at closest approach.

Its instruments are protected from the sun by a 11.43-centimetre carbon-composite shield, which can withstand temperatures reaching nearly 1,377 C.

It’ll continue circling the sun at this distance until at least September.

Scientists hope to better understand why the corona is hundreds of times hotter than the sun’s surface and what drives the solar wind, the supersonic stream of charged particles constantly blasting away from the sun.