Getty Images

Getty ImagesHundreds of Tibetans protesting against a Chinese dam were rounded up in a harsh crackdown earlier this year, with some beaten and seriously injured, the BBC has learnt from sources and verified footage.

Such protests are extremely rare in Tibet, which China has tightly controlled since it annexed the region in the 1950s. That they still happened highlights China’s controversial push to build dams in what has long been a sensitive area.

Claims of the arrests and beatings began trickling out shortly after the events in February. In the following days authorities further tightened restrictions, making it difficult for anyone to verify the story, especially journalists who cannot freely travel to Tibet.

But the BBC has spent months tracking down Tibetan sources whose family and friends were detained and beaten. BBC Verify has also examined satellite imagery and verified leaked videos which show mass protests and monks begging the authorities for mercy.

The sources live outside of China and are not associated with activist groups. But they did not wish to be named for safety reasons.

In response to our queries, the Chinese embassy in the UK did not confirm nor deny the protests or the ensuing crackdown.

But it said: “China is a country governed by the rule of law, and strictly safeguards citizens’ rights to lawfully express their concerns and provide opinions or suggestions.”

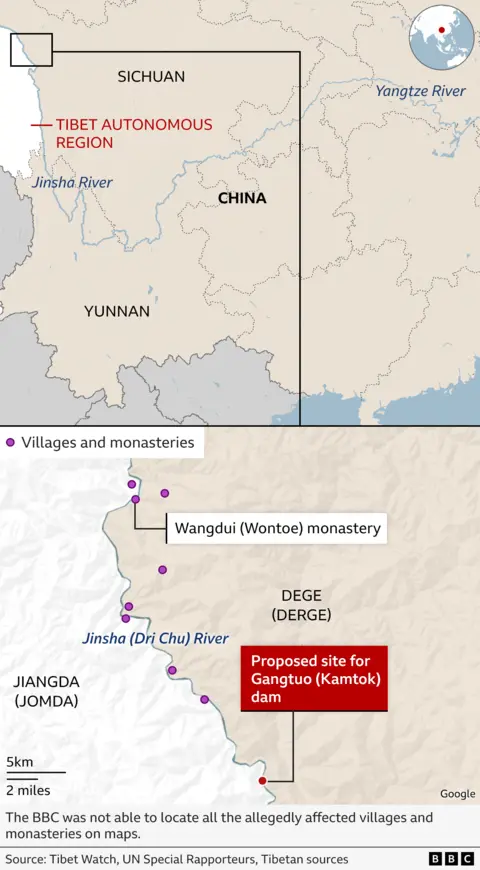

The protests, followed by the crackdown, took place in a territory home to Tibetans in Sichuan province. For years, Chinese authorities have been planning to build the massive Gangtuo dam and hydropower plant, also known as Kamtok in Tibetan, in the valley straddling the Dege (Derge) and Jiangda (Jomda) counties.

Once built, the dam’s reservoir would submerge an area that is culturally and religiously significant to Tibetans, and home to several villages and ancient monasteries containing sacred relics.

One of them, the 700-year-old Wangdui (Wontoe) Monastery, has particular historical value as its walls feature rare Buddhist murals.

The Gangtuo dam would also displace thousands of Tibetans. The BBC has seen what appears to be a public tender document for the relocation of 4,287 residents to make way for the dam.

The BBC contacted an official listed on the tender document as well as Huadian, the state-owned enterprise reportedly building the dam. Neither have responded.

Plans to build the dam were first approved in 2012, according to a United Nations special rapporteurs letter to the Chinese government. The letter, which is from July 2024, raised concerns about the dam’s “irreversible impact” on thousands of people and the environment.

From the start, residents were not “consulted in a meaningful way” about the dam, according to the letter. For instance, they were given information that was inadequate and not in the Tibetan language.

They were also promised by the government that the project would only go ahead if 80% of them agreed to it, but “there is no evidence this consent was ever given,” the letter goes on to say, adding that residents tried to raise concerns about the dam several times.

Chinese authorities, however, denied this in their response to the UN. “The relocation of the villages in question was carried out only after full consultation of the opinions of the local residents,” the Permanent Mission of the People’s Republic of China to the United Nations office said in a letter from September 2024.

It added: “Local government and project developers funded the construction of new homes and provided subsidies for grazing, herding and farming. As for any cultural relics, they were relocated in their entirety.”

But the BBC understands from two Tibetan sources that, in February, officials had told them they would be evicted imminently, while giving them little information about resettlement options and compensation.

This triggered such deep anxiety that villagers and Buddhist monks decided to stage protests, despite knowing the risks of a crackdown.

‘They didn’t know what was going to happen to them’

The largest one saw hundreds gathering outside a government building in Dege. In a video clip obtained and verified by the BBC, protesters can be heard calling on authorities to stop the evictions and let them stay.

Separately, a group of residents approached visiting officials and pleaded with them to cancel plans to build the dam. The BBC has obtained footage which appears to show this incident, and verified it took place in the village of Xiba.

The clip shows red-robed monks and villagers kneeling on a dusty road and showing a thumbs-up, a traditional Tibetan way of begging for mercy.

In the past the Chinese government has been quick to stamp out resistance to authority, especially in Tibetan territory where it is sensitive to anything that could potentially feed separatist sentiment.

It was no different this time. Authorities swiftly launched their crackdown, arresting hundreds of people at protests while also raiding homes across the valley, according to one of our sources.

One unverified but widely shared clip appears to show Chinese policemen shoving a group of monks on a road, in what is thought to be an arrest operation.

Many were detained for weeks and some were beaten badly, according to our Tibetan sources whose family and friends were targeted in the crackdown.

One source shared fresh details of the interrogations. He told the BBC that a childhood friend was detained and interrogated over several days.

“He was asked questions and treated nicely at first. They asked him ‘who asked you to participate, who is behind this’.

“Then, when he couldn’t give them [the] answers they wanted, he was beaten by six or seven different security personnel over several days.”

His friend sustained only minor injuries, and was freed within a few days. But others were not so lucky.

Another source told the BBC that more than 20 of his relatives and friends were detained for participating in the protests, including an elderly person who was more than 70 years old.

“Some of them sustained injuries all over their body, including in their ribs and kidneys, from being kicked and beaten… some of them were sick because of their injuries,” he said.

Similar claims of physical abuse and beatings during the arrests have surfaced in overseas Tibetan media reports.

The UN letter also notes reports of detentions and use of force on hundreds of protesters, stating they were “severely beaten by the Chinese police, resulting in injuries that required hospitalisation”.

Tsering Woeser

Tsering Woeser Tsering Woeser

Tsering WoeserAfter the crackdown, Tibetans in the area encountered even tighter restrictions, the BBC understands. Communication with the outside world was further limited and there was increased surveillance. Those who are still contactable have been unwilling to talk as they fear another crackdown, according to sources.

The first source said while some released protesters were eventually allowed to travel elsewhere in Tibetan territory, others have been slapped with orders restricting their movement.

This has caused problems for those who need to go to hospital for medical treatment and nomadic tribespeople who need to roam across pastures with their herds, he said.

The second source said he last heard from his relatives and friends at the end of February: “When I got through, they said not to call any more as they would get arrested. They were very scared, they would hang up on me.

“We used to talk over WeChat, but now that is not possible. I’m totally blocked from contacting all of them,” he said.

“The last person I spoke to was a younger female cousin. She said, ‘It’s very dangerous, a lot of us have been arrested, there’s a lot of trouble, they have hit a lot of us’… They didn’t know what was going to happen to them next.”

The BBC has been unable to find any mention of the protests and crackdown in Chinese state media. But shortly after the protests, a Chinese Communist Party official visited the area to “explain the necessity” of building the dam and called for “stability maintenance measures”, according to one report.

A few months later, a tender was awarded for the construction of a Dege “public security post”, according to documents posted online.

The letter from Chinese authorities to the UN suggests villagers have already been relocated and relics moved, but it is unclear how far the project has progressed.

The BBC has been monitoring the valley via satellite imagery for months. For now, there is no sign of the dam’s construction nor demolition of the villages and monasteries.

The Chinese embassy told us authorities were still conducting geological surveys and specialised studies to build the dam. They added the local government is “actively and thoroughly understanding the demands and aspirations” of residents.

Development or exploitation?

China is no stranger to controversy when it comes to dams.

When the government constructed the world’s biggest dam in the 90s – the Three Gorges on the Yangtze River – it saw protests and criticism over its handling of relocation and compensation for thousands of villagers.

In more recent years, as China has accelerated its pivot from coal to clean energy sources, such moves have become especially sensitive in Tibetan territories.

Beijing has been eyeing the steep valleys and mighty rivers here, in the rural west, to build mega-dams and hydropower stations that can sustain China’s electricity-hungry eastern metropolises. President Xi Jinping has personally pushed for this, a policy called “xidiandongsong”, or “sending western electricity eastwards”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLike Gangtuo, many of these dams are on the Jinsha (Dri Chu) river, which runs through Tibetan territories. It forms the upper reaches of the Yangtze river and is part of what China calls the world’s largest clean energy corridor.

Gangtuo is in fact the latest in a series of 13 dams planned for this valley, five of which are already in operation or under construction.

The Chinese government and state media have presented these dams as a win-win solution that cuts pollution and generates clean energy, while uplifting rural Tibetans.

In its statement to the BBC, the Chinese embassy said clean energy projects focus on “promoting high-quality economic development” and “enhancing the sense of gain and happiness among people of all ethnic groups”.

But the Chinese government has long been accused of violating Tibetans’ rights. Activists say the dams are the latest example of Beijing’s exploitation of Tibetans and their land.

“What we are seeing is the accelerated destruction of Tibetan religious, cultural and linguistic heritage,” said Tenzin Choekyi, a researcher with rights group Tibet Watch. “This is the ‘high-quality development’ and ‘ecological civilisation’ that the Chinese government is implementing in Tibet.”

One key issue is China’s relocation policy that evicts Tibetans from their homes to make way for development – it is what drove the protests by villagers and monks living near the Gangtuo dam. More than 930,000 rural Tibetans are estimated to have been relocated since 2000, according to Human Rights Watch (HRW).

Beijing has always maintained that these relocations happen only with the consent of Tibetans, and that they are given housing, compensation and new job opportunities. State media often portrays it as an improvement in their living conditions.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut rights groups paint a different picture, with reports detailing evidence of coercion, complaints of inadequate compensation, cramped living conditions, and lack of jobs. They also point out that relocation severs the deep, centuries-old connection that rural Tibetans share with their land.

“These people will essentially lose everything they own, their livelihoods and community heritage,” said Maya Wang, interim China director at HRW.

There are also environmental concerns over the flooding of Tibetan valleys renowned for their biodiversity, and the possible dangers of building dams in a region rife with earthquake fault lines.

Some Chinese academics have found the pressure from accumulated water in dam reservoirs could potentially increase the risk of quakes, including in the Jinsha river. This could cause catastrophic flooding and destruction, as seen in 2018, when rain-induced landslides occurred at a village situated between two dam construction sites on Jinsha.

The Chinese embassy told us that the implementation of any clean energy project “will go through scientific planning and rigorous demonstration, and will be subject to relevant supervision”.

In recent years, China has passed laws safeguarding the environment surrounding the Yangtze River and the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. President Xi has personally stressed the need to protect the Yangtze’s upper reaches.

About 424 million yuan (£45.5m, $60m) has been spent on environmental conservation along Jinsha, according to state media. Reports have also highlighted efforts to quake-proof dam projects.

Multiple Tibetan rights groups, however, argue that any large-scale development in Tibetan territory, including dams such as Gangtuo, should be halted.

They have staged protests overseas and called for an international moratorium, arguing that companies participating in such projects would be “allowing the Chinese government to profit from the occupation and oppression of Tibetans”.

“I really hope that this [dam-building] stops,” one of our sources said. “Our ancestors were here, our temples are here. We have been here for generations. It is very painful to move. What kind of life would we have if we leave?”

Additional reporting by Richard Irvine-Brown of BBC Verify

UPDATE: This story has been updated to include China’s response to the UN about the Gangtuo dam in a letter dated 12 September 2024.