BBC

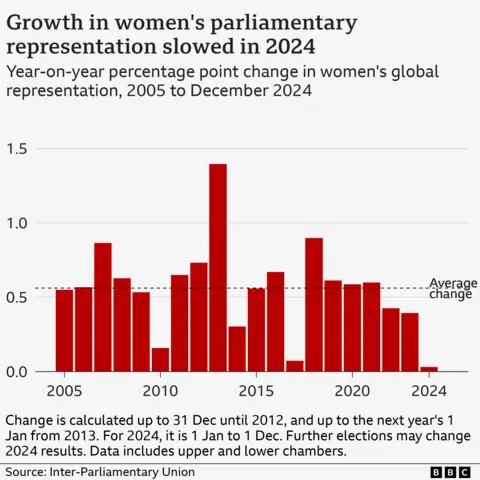

BBCNearly half the world’s population – 3.6 billion people – had major elections in 2024, but it was also a year that saw the slowest rate of growth in female representation for 20 years.

Twenty-seven new parliaments now have fewer women than they did before the elections – countries such as the US, Portugal, Pakistan, India, Indonesia and South Africa. And, for the first time in its history, fewer women were also elected to the European Parliament.

The BBC has crunched numbers from 46 countries where election results have been confirmed and found that in nearly two-thirds of them the number of women elected fell.

The data is from the Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU) – a global organisation of national parliaments that collects and analyses election data.

There were gains for women in the UK, Mongolia, Jordan and the Dominican Republic, while Mexico and Namibia both elected their first female presidents.

However, losses in other places mean that the growth this year has been negligible (0.03%) – after having doubled worldwide between 1995 and 2020.

Mariana Duarte Mutzenberg, who tracks gender statistics for the IPU, says progress has been “too fragile” in certain democracies. For example, the Pacific Island nation Tuvalu lost its only female member of parliament, and now has no women in government at all.

UNDP

UNDPThe Pacific Islands have the lowest proportion of female members of parliament in the world at 8%.

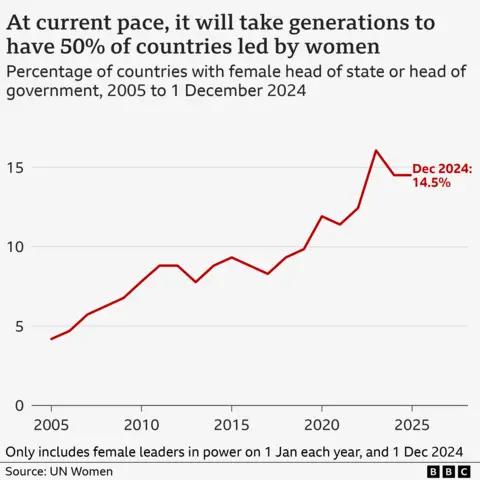

Globally, women make up 27% of parliaments worldwide, and only 13 countries are close to 50%. Latin America and parts of Africa are currently leading when it comes to female representation.

Some countries, says Ms Duarte Mutzenberg, are still making gains, largely thanks to gender quotas – Mongolia jumped from 10% to 25% female representation this year, after introducing a mandatory 30% candidate quota for women.

On average, countries without quotas have elected 21% women, compared with 29% with quotas.

For example, quotas – and political will – helped Mexico achieve gender parity in 2018, after former president Andrés Manuel López Obrador decided the parliament should be 50% women.

Political will could also be a game-changer when it comes to ministerial positions, says Julie Ballington from UN Women – which collects data on women heading government ministries.

Cabinets have the power to impact society, yet still have the lowest female representation of all the political measures UN Women looks at, she says, with women usually restricted to certain ministerial roles such as overseeing human rights, equality, and social affairs – rather than finance or defence.

This is “a missed opportunity”, she says.

With so many different countries, contexts and political intricacies at play it is hard to define why the dial hardly shifted this year.

But there are some universal barriers to women’s participation in politics.

Firstly, research has shown there is an ambition gender gap.

“Women are less likely to wake up and think they would be good in senior leadership,” professor of politics Rosie Campbell told an audience at King’s College, London. “They often need to be nudged: ‘Have you thought about being an MP?'”

And a slow-down could mean fewer mentors for future female politicians, says Dr Rachel George, an expert on gender and politics at Stanford University in the US. So young women would be “less likely to think that they can, or should, run”.

Once they do decide to run for office, women tend to be at a disadvantage financially.

A wealth of research has found it is harder for women to access funding for a political campaign or to have the financial freedom to take time off work.

In most societies, women still have more caring responsibilities than men – which can negatively affect how they are viewed by voters, says Dr George.

This is not helped by the fact that few parliaments offer maternity leave, says Carlien Scheele from the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). “It puts women off if those policies are not in place,” she says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd then, there is the way electoral systems are designed.

Countries using proportional representation (PR) or mixed electoral systems elect a higher share of women than first-past-the-post systems and are also more likely to have electoral quotas for women, according to the IPU.

But those factors are not new. So what is changing?

There has been an increase in attacks on women in public life, online and in person, according to studies in many different countries.

In Mexico, which already experiences violent elections, gender-based violence was particularly high this year, says IPU’s Mariana Duarte Mutzenberg, with women politicians also particularly targeted by disinformation aimed at “trying to ruin their reputation in one way or another”.

This all has a wider “chilling effect” and stops younger women from wanting to run, says Dr George.

A backlash to female economic empowerment and feminism is also a factor.

In South Korea – despite a small increase in the share of women elected – a feeling among many young men of reverse discrimination played out in this year’s election.

“Some parties continued to fuel or tap into an anti-gender sentiment among male voters who perceive women’s rights advocates as anti-men,” says Ms Duarte Mutzenberg.

However, she says, this may have led to even more women coming out to vote.

So why does it all matter?

Basic fairness aside, equal parliaments could improve national economies, says EIGE’s Carlien Scheele, citing research showing gender diverse groups make better decisions, and gender-mixed boards lead to higher profits.

Studies have also shown the benefits of including women in peace negotiations, suggesting that processes which are based on substantive contributions from women are more likely to achieve sustainable outcomes.

“When women are in the room, peace deals are more likely to happen and more likely to last,” says Dr George.

Julie Ballington from UN Women says she would encourage people to think about women in politics differently.

“It’s not the under-representation of women. It’s the over-representation of men.”

Additional data analysis by Rebecca Wedge-Roberts from BBC Verify

Design by Raees Hussain